A new website has been launched, designed to help veterinary assistants find the education they need. The following is a sample of the first lesson of Veterinary Assistant 1: Becoming a Veterinary Assistant.

Your Role at the Hospital

Your Role at the Hospital

The attitude and abilities of the veterinary staff can make or break a practice just as easily as the behavior and knowledge of a veterinarian can. I believe that a well-informed, personable veterinary team member who can advise clients correctly is a true asset to every veterinary hospital, and this is what my course is all about.

You may be wondering what role everyone at the hospital has and how you can fit in. Let’s look at each person and what they do.

The veterinarians are the ones who decide on patient care. This is what I do. Unless you are ready to go to university for many years, you won’t become a James Herriot. For those of you who don’t know who this fictional veterinarian is, I guess I’m dating myself.

As you walk into a veterinary hospital, you’ll see and speak to the receptionist. Her varied role includes setting appointments, admitting patients, doing billing and payments, and giving advice on animal health topics. There are short courses available at some colleges to learn these skills, but most receptionists are trained on the job.

The veterinary technologist (or technician) works directly with the patients. She might be pulling a blood or urine sample, taking a radiograph, watching a patient under anesthetic, assisting with a dental procedure, or doing minor surgery. She’s gone through an intensive two-year college course. There are some distance education opportunities for “techs” now, but their availability depends on where you live.

The veterinary assistant is likely the one you want to know about. If you become one, your role is to assist anyone in the hospital who needs it. If the tech wants to take blood, how do you restrain the cat? If a dog neuter is the next surgery, what do you need to set up for it? How do you take a lateral radiograph of a cat’s chest? What do you tell Mrs. Smith about the worms and fleas her dog has? Can you give advice on what to feed a geriatric cat?

I have designed my courses to teach you how to assist in all these duties. When you’re looking for a job, they’ll give you an advantage over other applicants so that you can become employed at a veterinary hospital. I’ve also had many students who are already working with a veterinarian but they want to bolster their knowledge to do their job more effectively.

Some students wonder about veterinary assistant certification. There is an Approved Veterinary Assistant (AVA) designation provided by the National Association of Veterinary Technicians in America (NAVTA). To get this, you need to attend a college that offers the programs. These programs are commonly associated with veterinary technician programs. The alternative is doing it through distance education if you’re employed at a veterinary hospital, again through NAVTA.

If you don’t live where you can take an AVA program, can’t afford the time to attend classes, or don’t work at a veterinary hospital, this is the alternative. I teach three six-week Veterinary Assistant courses and also a lengthier course (three to six months depending on how fast you do it), which are all available through your college. You can get information on these courses by checking the college website. I will provide links to more information on these courses at the end of Lesson 12 before we finish up this course.

Chapter 3

Back to the Basics: Canine and Feline Reproduction

Since cats and dogs have become such important members of our families, participating in responsible animal reproduction is often part of the pet owning experience. Responsible breeding means that you have your animal checked out by a professional who can identify any defects in your animal that might be passed on to its offspring. If your pet suffers from hip dysplasia, poor eyesight, or any other number of genetic diseases, they should not be bred. Period.

Your next step as a responsible pet owner is to have your pet spayed so that these weaknesses aren’t passed on. It may sound cruel; however, many of the genetic diseases found in the most popular breeds, like Golden Retrievers or German Shepherds, are a result of people breeding animals that are genetically imperfect. This can mean a lifetime of pain and illness for the animals and thousands of dollars in bills for the owner.

Finally, it’s also important to make sure you have enough loving families to send your puppies or kittens to. This will avoid unwanted pets that have to be euthanized or who go feral if they’re released to fend for themselves.

With this information in mind, let’s begin to look at some key glossary terms related to breeding.

Canine Breeding: Female and Male

A recurring question from owners with new puppies is, “When will my dog come into heat?” Unfortunately, there’s no single answer that applies to all dogs. Females have their first heat once they reach sexual maturity, but this depends on the breed and the size of the dog. In small dogs, the first heat occurs when pups are between six and ten months of age. In giant breeds, such as Great Danes, it isn’t uncommon for a female to start cycling at 16 to 20 months.

When a female starts her cycle (a four-step process), she begins the proestrus stage, and the first noticeable sign is a swelling of the vulva. Many owners miss this stage, especially if the dog is long-haired. But they rarely miss the next sign: bleeding from the vulva. This vaginal discharge attracts male dogs but the female rarely allows mating during this phase of her cycle. She is more inclined to attack a male who is too forward.

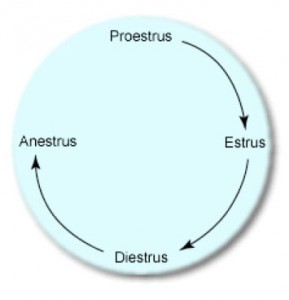

Here are the stages of a normal estrous cycle:

Here are the stages of a normal estrous cycle:

Proestrus begins the estrous cycle. This is followed by estrus, diestrus, and anestrus.

After about nine days of proestrus (it can range from three to fourteen days), estrus begins. This is technically the heat. The vaginal discharge changes from bloody to clear or pink. It’s during estrus that ovulation occurs, so the female will be more receptive and will allow the male to approach and breed. The estrus phase lasts for about a week, though it can range from two days to twenty.

If a female dog isn’t bred, or is bred and does not become pregnant, she enters a short stage called diestrus. Some can go through a false pregnancy during this time. They think they’re pregnant so they eat more and put on weight as if they’re expecting. When the 63-day mark rolls around, they grab a ball or stuffed animal and carry it around like it is a pup. Many produce milk for the puppies they believe they carry. I’ve even seen a few who go into labor, complete with contractions.

Pregnancy is technically a diestrus as well, but we refer to it as pregnancy. Interestingly, the hormone fluctuations that occur during pregnancy, false pregnancy, or plain diestrus are indistinguishable.

Once diestrus is finished, the female enters a period of hormonal dormancy, called anestrus, between her heat cycles. The average length of this stage is four months (making the entire cycle roughly 7 months long). The complete estrous cycle varies from five to twelve months. For some, it’s even longer.

When the Time is Right

Although there are many days when a dog can successfully mate, some days are better than others. To help ensure a successful breeding, a veterinarian can do a vaginal smear. In this procedure, a sterile cotton swab is inserted into the vagina. The cells collected on the swab are transferred to a microscope slide, stained and analyzed. The type of cells present indicate when she is going to ovulate.

Another way to pinpoint the best breeding time is by checking blood hormone levels. We’re looking for a rise in the progesterone level to tell us when ovulation is about to occur. You’ll see a reference periodically to Luteinizing Hormone (LH). It’s produced by the pituitary gland, and when it peaks, it triggers ovulation. As such, it’s often used as a marker for when ovulation occurs and events are tracked from that time. Because the testing for LH is done in laboratories, it’s used more for research than practically.

The old way to get the best chance of conception is to give the female access to the male every second day during her estrus until she will no longer stand for breeding. This still works very well and it avoids testing.

If the dog becomes pregnant, she can look forward to a gestation (pregnancy) of about 63 days. The actual length of pregnancy is determined by the number of puppies because they trigger birthing. If there are more puppies, the gestation is shorter. If there are fewer puppies, the pregnancy will be longer. In fact, if there is only one pup, pregnancy can extend up to 68 days. If there is only one or two pups, they can grow very large, both from the extended time in the uterus and the additional nutrition they get because of lack of competition inside the uterus. Large pups make birthing (whelping) more difficult. A caesarean section (C-section) may be needed if the pups are too large to pass through the birth canal.

The male’s mission in life follows a much more simple path: produce sperm to impregnate the egg. He can start doing this when he is sexually mature. This occurs at about the same age that the female (of the same breed) commences her cycles. Males can maintain their fertility well into their senior years. Females often stop cycling as they age, but pregnancies in dogs up to eight years old are possible.

Feline Reproduction: Female and Male

Cats are very efficient reproductive machines. I’ve seen tiny kittens in heat as early as four months of age who then give birth when only six months old. I’ve also seen cats pregnant while they’re still feeding the kittens from their last litter. There’s no doubt about it—cats can reproduce very quickly!

Most cats are six to seven months old when they start their cycling, but this varies with the time of year that they reach this age. If a kitten is six months old in October, she probably won’t cycle until she is eight or nine months old because the lengthening of days in the spring is an important trigger.

Most cats are six to seven months old when they start their cycling, but this varies with the time of year that they reach this age. If a kitten is six months old in October, she probably won’t cycle until she is eight or nine months old because the lengthening of days in the spring is an important trigger.

The effect of light on breeding cycles isn’t restricted to cats. We also see it in rabbits and rodents. Nature is smart to arrange it this way. A part of the brain called the pineal body senses light and drives hormones. As it senses longer days (after December 21), it gets the cycles going. In the case of cats, they come into heat in about February or March. The kittens would be born in April or May. This is timed so that there is also a food source—lots of mice and such—that are also exploding in population.

In the northern hemisphere, the feline breeding season roughly starts in January and continues into September. A cat’s estrous cycle has the same four phases as a dog’s so I won’t repeat this information again, but I will tell you what the differences are between the two species.

The proestrus part of a queen’s cycle is inconspicuous, but owners don’t miss the estrus stage. Cats in estrus often appear to be in pain and their owners sometimes rush them to the hospital because they howl and roll about as if in pain. Cats do this because they’re crying for a mate, not because of an illness or injury. Cats in this stage usually pull their tails up and raise their rumps if you touch them over the hips or back.

When to Mate

A queen is receptive to a male for about seven days during estrus. She does not ovulate unless she copulates with a male. A male has small spines on his penis that ensures the female knows she has been bred. This induced ovulation ensures that none of the queen’s eggs are ever wasted. If a queen isn’t bred, she continues to show signs of heat about every three weeks.

The length of pregnancy in cats varies from 64 to 69 days. The average number of kittens per litter is four. Younger queens tend to have smaller litters than older queens.

To determine if a queen is pregnant, I prefer to feel for the kittens (what we call palpation). This is most accurate between 18 and 28 days after the breeding. This is because the feti (plural for fetus) and the fluids surrounding them feel like small ping pong balls. Before this time, the feti are too small to feel, and after 28 days, so much fluid surrounds the fetus that it can be hard to differentiate pregnancy from a uterine infection. Radiographs can be used to verify the number in the litter once the kittens’ bones have calcified (over 45 days into the pregnancy). The same methods can be used in the dog.

To determine if a queen is pregnant, I prefer to feel for the kittens (what we call palpation). This is most accurate between 18 and 28 days after the breeding. This is because the feti (plural for fetus) and the fluids surrounding them feel like small ping pong balls. Before this time, the feti are too small to feel, and after 28 days, so much fluid surrounds the fetus that it can be hard to differentiate pregnancy from a uterine infection. Radiographs can be used to verify the number in the litter once the kittens’ bones have calcified (over 45 days into the pregnancy). The same methods can be used in the dog.

Male cats become fertile at the same age as queens; that is, six to seven months of age. Though I’ve had clients swear this shouldn’t happen because it isn’t proper, male kittens can and will breed their mothers. Kittens that are to be kept with their mothers should be neutered, which is the topic of the next chapter.

Chapter 4

Reproduction: How and Why Should We Stop It?

There’s an old wives’ tale that I must overcome when I talk to clients about spaying and neutering. Some people still think that dogs make better pets if they have a litter or a heat first. I don’t believe this and I haven’t found any data to support this statement.

Sterilization is the most important surgery a dog or cat will have in its life. It’s an accepted form of birth control, but just as importantly, it has medical benefits for both males and females.

There are two reasons for wanting to spay a female cat or dog. One is to stop them from contributing to the pet population. Take a trip to a local shelter and you will quickly see that there are too many unwanted cats and dogs in the world.

Sadly, one part of my job was to euthanize cats at an overcrowded shelter. On one of these visits, I entered the room and was greeted by 25 faces. All of them were destined to die. Ever since these experiences with this side of animal care over 20 years ago, …

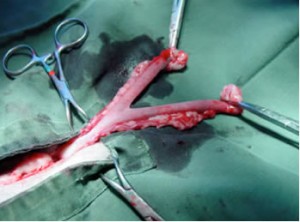

In females, sterilization is also sometimes called a castration or neuter. But, because a female is sterilized by removing both her uterus and ovaries, and we want to be technically correct, we use the term ovariohysterectomy. Another word you’ll see is a spay, but this should only apply if the veterinarian is only removing the two ovaries (and leaves the uterus intact).

In females, sterilization is also sometimes called a castration or neuter. But, because a female is sterilized by removing both her uterus and ovaries, and we want to be technically correct, we use the term ovariohysterectomy. Another word you’ll see is a spay, but this should only apply if the veterinarian is only removing the two ovaries (and leaves the uterus intact).

When a female is sterilized, there are no ovaries left to produce hormones, which means there is no estrous cycle. Females will not come into heat and the mammary glands do not undergo the changes that predispose them to tumor formation. Also, with an ovariohysterectomy, there is no uterus remaining so it totally prevents pyometra.

I recommend performing these surgeries when my patients are six months of age when the adult teeth have erupted. This is before the females come into heat and before the males develop annoying behaviors.

What will the future bring? Researchers continue to focus their efforts on developing a vaccine to prevent pregnancy. One of the products currently being developed works by stimulating immunity against parts of the developing egg. Although they won’t become pregnant, females will still cycle. In the years to come, these products may have a place in helping us control animal population, especially in areas that do not have regular veterinary services, making a better quality of life for our pets.

For more information on the Veterinary Assistant Learning Center, click here.

Dr. Louise Janes D.V.M. & Dr. Jeff Grognet D.V.M

Mid-Isle

Mid-Isle

Veterinary Hospital

5-161 Fern Road

West Qualicum Beach, BC

Tel (250) 752-8969

Veterinary Assistant Learning Center

See all articles by Dr. Louise Janes D.V.M. & Dr. Jeff Grognet D.V.M.

Our son is wanting to take the next step towards becoming a VA, however, he can’t get placement here and we cannot afford him to go to school elsewhere, what do you suggest?

Very interesting article. I enjoyed the lesson in pet cycles.