Veterinary medicine has ancient roots. In early Roman days, animal caretakers were called souvetaurinarii – the origin of the word veterinarian. Because the only valuable animals were ones that could be eaten or ridden, early medical practice was restricted to horses, cattle, pigs, and sheep.

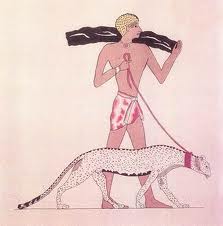

Cats were honored and cared for in ancient Egypt but little attention was directed to dogs. It was not until Medieval times in Europe that medical care for hunting dogs became an acceptable practice.

Cats were honored and cared for in ancient Egypt but little attention was directed to dogs. It was not until Medieval times in Europe that medical care for hunting dogs became an acceptable practice.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, economics demanded that veterinary practitioners focus on cattle and horses. People didn’t spend much money on dogs, and the expendable cat was only useful for keeping the vermin down in the barns.

Only dogs raised by the wealthy received “medical attention”. Unfortunately, that veterinary care was sadly lacking. Many dogs died not only from their diseases but also from the treatments imposed on them.

The internal combustion engine changed not only the world of transportation but also the field of veterinary medicine. As horses dwindled in numbers, veterinarians had to find something else to do. They turned their attention to a species they had previously ignored.

Canine practice has evolved over the last 50 years. Initially, large animal practitioners treated dogs purely as a sideline. As dogs gained importance as family members, veterinarians responded. They learned to appreciate the virtues of their canine patients, setting up practices devoted exclusively to the care of companion animals.

To grasp the enormity of the progress made in canine practice, it is important to appreciate the standard of practice employed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A modern-day animal-lover would be appalled at the superstition-based, barbaric practices of that period.

The importance of worming dogs was as important in the late 1800s as it is today, but the procedures employed are poles apart. The development of orally administered parasiticides has made it easy, effective, and safe to deworm puppies today. Pups wormed in the late 19th century weren’t so lucky. Because tail ligaments were wrongly assumed to be worms, “worming” consisted of “biting off the last bone in the tail and drawing out the sinew”. Once completed, pups were not only supposed to be worm-free; they were also considered immune to rabies!

Today, clients expect the same level of care for their pets as they do for themselves. This has stimulated veterinarians to keep up to date with the ever expanding knowledge base of medicine and surgery. It has also led to the demand for advanced care by board certified veterinarians who specialize in specific areas of companion animal practice, from ophthalmology, through internal medicine, to behaviour.

Luckily, veterinary medicine has evolved. Much of the initial progress in small animal practice has been credited to an 1892 graduate of the Royal Veterinary College named Frederick G.T.Hobday. He devised a humane technique for securing dogs before induction of anesthetic and also a way to control the amount of chloroform vapour delivered to dogs under anesthesia. The result of these innovations was a significant reduction in anesthetic deaths. Prior to this time, most procedures, some very painful, were performed without anesthesia because veterinarians were uncomfortable with the risks of general anesthetics.

In 1915, an American veterinarian published a protocol for a canine ovariohysterectomy (spay). He included the recommended anesthetic technique as well as a description of the surgical procedure. He also discussed the benefits of performing the surgery on a horizontal operating table. Before his insightful counsel, veterinarians routinely suspended dogs by their hind legs from a hook on the wall to do abdominal surgery. In that position, the patient’s abdominal organs put pressure on its heart and lungs. Not surprisingly, many dogs succumbed to cardiopulmonary collapse. Despite the success of these progressive changes in the field of canine surgery, the problem of post-surgical infections persisted until the adoption of sterile surgical techniques and the introduction of antibiotics.

Throughout his lifetime, Hobday continued to have a far reaching effect on the practice of veterinary medicine. He introduced the x-ray machine to the veterinary community, allowing better diagnosis and treatment of fractures. He also pioneered research on canine distemper, helping to develop the first vaccine against this deadly viral disease. In 1928, a distemper vaccination program involved the administration of a dose of killed distemper virus followed a week later by a dose of the live virus. Canine distemper vaccines have been modified over the years, becoming safer and more effective.

Throughout his lifetime, Hobday continued to have a far reaching effect on the practice of veterinary medicine. He introduced the x-ray machine to the veterinary community, allowing better diagnosis and treatment of fractures. He also pioneered research on canine distemper, helping to develop the first vaccine against this deadly viral disease. In 1928, a distemper vaccination program involved the administration of a dose of killed distemper virus followed a week later by a dose of the live virus. Canine distemper vaccines have been modified over the years, becoming safer and more effective.

The veterinary professionals’ focus on infectious disease has broadened and intensified with the passing of each decade. When canine Parvovirus broke in 1978, effective vaccines were quickly developed and marketed. The arsenal aimed at canine infectious disease continues to expand with the recent release of vaccines against Lyme Disease and Giardia.

The real impetus for the “birth” of canine medicine was the dwindling horse and cow population. Initially, veterinarians did just a little canine practice on the side to fill their time, but as attitudes towards small animals changed, practices devoted solely to small animals began to emerge. By 1933, shifting perspectives spurred the formation of the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA). This association was, and continues to be, instrumental in establishing standards for veterinary hospitals and for veterinary care of companion animals.

Even after canine medicine was established as a viable branch of veterinary medicine, the amount of information on dogs dispersed to practitioners each year was initially miniscule. Despite this slow start, there were still some profound medical and surgical breakthroughs. As well as major innovations in fracture repair, there were advancements in the recognition and understanding of a number of orthopedic conditions.

For example, German Shepherds used for sentry duty during the Second World War were found to break down during training. X-rays revealed a characteristic change in the hip joint that was later coined “hip dysplasia”. Continued research revealed that this was a genetic condition. Over the ensuing years, a radiograph screening program was developed to help breeders reduce the incidence of this crippling condition in their breeding lines.

In the 1960s, the first textbooks devoted solely to canine medicine and surgery were released. These publications provided veterinarians with the most up-to-date information. Today, continuing education is readily available not only through texts, but also through journals, seminars taught by leading experts, and Internet courses offered by veterinary colleges.

The first formal postgraduate training program for any veterinarian was offered at the Ontario Veterinary College. It was a surgical residency under the tutelage of a veterinarian who had learned surgical techniques through study in the human field. Today, veterinarians can complete residencies in a number of specialized areas. They can then become board-certified in such fields as dermatology, radiology, ophthalmology, internal medicine, anesthesiology, behaviour, pathology, oncology, and even dentistry.

The increasing availability of board-certified veterinarians has boosted the quality of care. A dog with a perplexing skin condition can be referred to a board-certified veterinary dermatologist for assessment. A dog that needs an intricate surgery, such as a joint replacement, can be treated by a veterinary orthopedic surgeon. A geriatric dog with an enlarged kidney can have a noninvasive ultrasound interpreted by a radiologist. An extremely fearful dog can be sent to a veterinary behaviourist for assessment and behaviour modification. And, of course, we are seeing a parallel increase in knowledge in the feline world.

Companion animal practice may have had a slow start, but it is now in full acceleration. Our four-legged companions now receive medical care that parallels that offered in the human field. At the turn of the century, removing a cataract from a dog’s eye to restore vision would have been inconceivable. Today, it is almost considered routine. With that in mind, imagine the possibilities of veterinary practice a hundred years from now.

Companion animal practice may have had a slow start, but it is now in full acceleration. Our four-legged companions now receive medical care that parallels that offered in the human field. At the turn of the century, removing a cataract from a dog’s eye to restore vision would have been inconceivable. Today, it is almost considered routine. With that in mind, imagine the possibilities of veterinary practice a hundred years from now.

Dr. Louise Janes D.V.M. & Dr. Jeff Grognet D.V.M

Mid-Isle Veterinary Hospital

Mid-Isle Veterinary Hospital

5-161 Fern Road West

Qualicum Beach, BC

Tel (250) 752-8969

See all articles by Dr. Louise Janes D.V.M. & Dr. Jeff Grognet D.V.M.